The Natural Choice that Manages Weeds and Builds Soil Health

Download pdf: Successfully Controlling Noxious Weeds with Goats

By Lani Malmberg (formerly Lani Lamming), is the Co-founder of the Goatapelli Foundation and was a Beyond Pesticides board member. She has an M.S. in weed science from CSU in Ft. Collins, Colorado. Original publication: Beyond Pesticides, National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides, Page 20 Pesticides and You Vol. 21, No. 4, 2001.

Alternative Weed Strategies

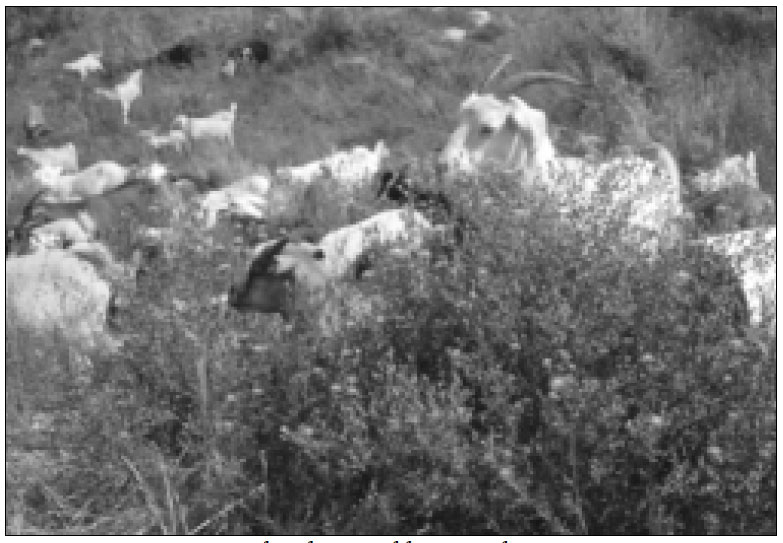

I am a displaced cattle rancher. I bought a hundred head of cashmere goats to eat weeds in 1997 because I could not find a job that I wanted or that suited me. I now have 2,000 head of goats and have 12 people working for me. The goats are used as a tool in intensive grazing and short-duration schemes under holistic resource management principles.

The goal of the land is to build the soil so it can produce the kinds of plants that we want to grow there. What we need to be looking at is the water cycle, mineral cycle, energy flow, and succession. Weeds are symptomatic of a problem. The problem is sometimes poor soil has no organic matter that cannot support good growth. We want to make the grass the best competitor and stress the weed at every turn. Goats help with this problem because everything they eat is then recycled as a fertilizer and laid back down on the grasses. As the goats graze, they trample on the fertilizer.

We worked last year in seven states. I keep working and moving from job to job, migrating north to south, and up and down in elevation; working all the time. I have federal contracts with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Forest Service. I have state, county, and city contracts in several states. But, most of my business is on private land. The smallest area I have grazed was a 12-foot by 60-foot backyard. I grazed 30 baby goats there for three days. The biggest job I have done was 20,000 acres in Montana.

We take a lot of data while we are herding goats. We use a video camera with a GPS unit hooked into it. I am able to create a noxious weed layer that can go into any government database for their noxious weed inventory.

Problems with pesticides

To a cattle producer, there is no production on land that is covered with noxious weeds. Therefore, he/she has to rent property to feed his cattle. Because the law requires him to clean it up, he will probably spray Tordon (picloram and 2,4-D) on it, costing him about $100 an acre. I have seen patches of land sprayed with this pesticide, killing everything but the diffuse knapweed it was meant to kill. Now the cattle producer has got two-fold costs and no production.

When you introduce humans after weed problems, you tend to have lots of trouble with human error. First, they have to recognize the weeds, which they probably will not be able to do unless it is in full flower. Then, they have to get the right eradication method on the right day and at the right time to get it done.

One problem with using chemicals to control weeds is that they are trying to kill the symptom. Pesticides never take care of the problem. The problem is that there is a stress or a niche open on the land that needs to be filled with something good, something productive that you want.

A lot of things happen when you spray pesticides. For one, the weeds can mutate and become deformed. I have seen this happen to common mullein. The spray boom along the highway got the plant and half of it deformed while the other half kept on growing. I have seen deformed prickly lettuce that was very thick-stemmed and curvy. The Roundup (glyphosate) that was sprayed on it did not kill it. Instead, it came back and made full seed. Another example is Dalmatian toadflax, which is normally tall and whisky. It was sprayed with a chemical called Curtail (clopyralid, 2,4-D) and it mutated into a ribbon. It was three inches wide and almost six feet tall and still had full flowers. I wonder what the genetics are of these plants.

On my master’s research plots in Wyoming, there are dead trees as a result of Tordon being sprayed ten years ago. The spraying also made a pure monoculture of Russian knapweed across the valley. The plot was then sprayed with a chemical to kill the Russian knapweed and reseeded with grasses. Every time a chemical was used to kill the Russian knapweed, white top, another noxious weed, began to grow there.

For some noxious weeds, chemical sprays are ineffective. One example is oxide daisy, which has no leaf surface for the chemical to be absorbed. But, goats love it.

Goats – the natural choice

My goat grazing service benefits are three-fold: environmental, economic, and social. Of course, environmental, because you can reduce chemicals or get rid of them completely. Economical, because we have put a lot of people to work, young kids, college students, high school kids, elementary students, and transients. And social, because there is nothing like a 1,000 head of goats to draw people into the land to learn about weeds.

Goats prefer weeds, like the knapweeds and yellow star thistle. They do not like grasses; it is their last choice. A goat has a very narrow triangular mouth and they pick, nibble, and chew very fast. The shape of their mouth and how they chew crushes almost everything they eat as far as weed seeds go. In the case of leafy spurge, a journal article says, when a goat eats 100% viable leafy spurge seed, 99.9% is destroyed.¹ Most is crushed by the teeth and chewing action, the rest through the digestive system.

Examples of weeds goats like:

Canada thistle

Cheat grass

Common candy

Common mullein

Dalmatian toad flax

Dandelions

Downy brome

lndian tobacco

Knapweeds

Larkspur

Leafy spurge

Loco weed

Musk thistle

Oxide daisy

Plumeless thistle

Poison hemlock

Purple loostrife

Scotch thistle

Snapweed

Sweet clover

Yellow star thistle

Yucca

For some noxious weeds, chemical sprays are ineffective. One example is the oxide daisy, which has no leaf surface for the chemical to be absorbed. But, goats love it.

Once the goats graze the weed, it cannot go to seed because it has no flower and it cannot photosynthesize to build a root system because it has no leaves.

Goats eat all poisonous plants, which does not seem to bother them. They have an interesting array of enzymes in their gut that other animals do not. In the case of poison hemlock, goats have an enzyme in the saliva that detoxifies the toxin before they swallow.

The first thing goats do when they walk through the pasture is snap off all the flower heads. Then they pick the leaves off one at a time, very quickly, leaving a bare stock. Once the goats graze the weed, it cannot go to seed because it has no flower and it cannot photosynthesize to build a root system because it has no leaves. The plant’s stalk and the ground is left undisturbed. The canopy has been removed allowing sunshine to hit the ground. The goats are fertilizing the ground, and the grasses remain untouched by the goats. Our working goats know when they are done and ready for the next job.

It is well-documented in research that if you cut the stems off of most weeds with a sharp blade the plant will quickly respond by making just as many seeds if not more, actually making the plant denser. But because of the way a goat eats, the plant is stopped. It cannot make any seeds or photosynthesize. I think the plant is fooled that everything is okay, so it does nothing.

The grazing selectivity is the goats diet preference. One thing we have learned is that goats have great diet specificity by age and gender. The older males preference for what they eat first differs from the baby goats, the nannies, and yearlings. If available, the older males prefer Russian thistle and Russian olive and elm trees, while the babies’ first choice is field vine weeds. At one of our jobs in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, we had two noxious weed problems, Musk thistle, and Lupin. The older male goats started grazing the Musk thistle and the younger goats started grazing the Lupin, a poisonous plant.

Timing must be right

Timing of when to graze a weed is important to make the biggest impact. If wildflowers are your goal for the land, yet you have to control your noxious weeds by law, I would graze to stress the weed when the wildflowers were not yet in bloom. For diffuse knapweed, the optimum time to graze is the first of June.

For Canada thistle, the perfect time to graze would be right when it is in full bud before it flowers. At this time, the plant has put all of its energy into getting ready to make a seed, so it has spent a lot of its root reserves. Over time, the thistle cannot compete with the grasses. Every time I stress the plant by grazing the goats, it will spend more energy trying to grow back. If you do this for a deep-rooted perennial for three times a season or over three years in a row, that plant has spent everything it has and will die.

Handling goats

When you are managing a 1,000 head of goats, you have to be able to handle them. We manage the goats by herding them within electric fences. Once the goats accept the fence as its boundary, it is magical stuff. On occasion, we do not turn them on.

Another way we handle the goats is by walking them. For one job, we walked 1,000 head of goats 35 miles down the right of- way of Highway 287 on our way to a ranch in Enis, Montana. Every landowner along the way came out, saw what we were doing, and hired us. So we stopped one day here, two days there, three weeks there. On our way, we grazed the goats on three islands in a river that was filled with spotted knapweed.

And Goats do not like water. It is a natural fence. The only time they will step into it is if a predator is in hot pursuit. Therefore, we had to figure out how to get the goats to the islands to graze. We found some picnic tables and placed them end-to-end across the river. Sure enough, that 1,000 head of goats used the picnic tables to get to each island and back to the mainland.

Leafy spurge – goats’ first love

Noxious weeds are extremely aggressive and invasive and are very difficult to control. Leafy spurge is a deep-rooted perennial and has an extensive root system. The seed capsules dry and shoot the seeds eight feet in all directions.

Another way we handle the goats is by walking them. For one job, we walked 1,000 head of goats 35 miles down the right-of-way of Highway 287 on our way to a ranch in Enis, Montana. Every landowner along the way came out, saw what we were doing, and hired us.

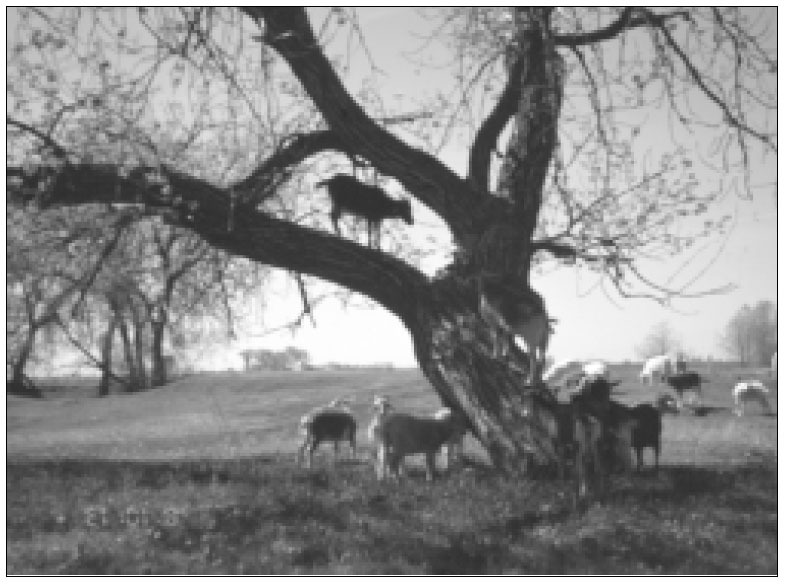

The extensive underground root system is also a spreading threat at the same time. Leafy spurge is capable of making an identical new plant far away from the mother plant. The root system goes down about 30 feet. It can grow in a crack in a rock, side of a cotton wood tree in the bark, or top of a cottonwood tree about 20 feet off the ground. What is the solution to leafy spurge in the cottonwood tree? Goats! Of course, leafy spurge is almost the goat’s favorite food and they do climb trees.

A great way for communities to recycle Christmas trees is to have people pay $2 to have goats recycle them. Any money generated could then be used for weed control in that community the following summer.

The goats seek out leafy spurge and eat it because they like it. When you look at a leafy spurge plant after the goats have grazed it, you can see where they have bitten the flower off, releasing a white latex substance. This white latex is supposed to make people go blind, cause rashes on hands, and cause blisters on horses’ feet. A little girl was sent to the hospital with third-degree burns from the white latex getting on her legs. This substance is the reason why cattle and horses will not eat it. Cattle will not even walk into the patches of leafy spurge. For some reason, it is the reason why goats eat it and love it.

Christmas tree recycling

A great way for communities to recycle Christmas trees is to have people pay $2 to have goats recycle them. Any money generated could then be used for weed control in that community the following summer.

The goats love Christmas trees, they clean it up and strip all the bark off. The remaining tree trunk could be sold to a youth group, to be cut, packaged, and sold as firewood. So recycling keeps going on and on through all levels of insects, birds, people, and different groups of people.

¹ Sedivec, K. et al. 1995. Controlling Leafy Spurge Using Goats and Sheep. North Dakota State University Extension Service, Fargo, North Dakota.

For more information, contact Lani Malmberg, Goat Green LLC at PO Box 657 Wellington, CO 80549, Phone 970-658-9495 or Ewe4icBenz@gmail.com.